The NISM institute federates the research activities of the chemistry and physics departments at the University of Namur. Research at the NISM institute focuses on various research topics in organic chemistry, physical chemistry, (nano)-materials chemistry, surface sciences, optics and photonics, solid state physics, both from a theoretical and an experimental point of view.

The institute's researchers have recognized expertise in the synthesis and functionalization of innovative molecular systems and materials, from 0 to 3 dimensions. They develop analytical and numerical modeling tools for the rational design of molecules and (nano)-materials with specific architectures that confer functional final properties.

They are supported by a technology park of advanced experimental techniques for studying the chemical and physical properties of these systems at micro- and nanometric scales. The research carried out within the institute falls within the field of both fundamental research, aimed at understanding and predicting the properties of structured matter, and applied research, with the aim of developing functional materials and devices.

NISM's lines of research are currently grouped into four poles, whose perimeters are flexible, reflecting the transdisciplinarity of the research themes and the collaborative dynamic between poles.

Each cluster is represented by a permanent scientist and a non-permanent scientist who, together with the institute's president and vice-president, form the institute's executive committee.

The institute's executive committee is made up of the president and vice-president of the institute.NISM research poles

Research at NISM is identified by four poles which highlight the main scientific activities carried out within the institute. Each pole is a well-defined structure with members, and is managed by the pole representative. The structuring of the pole does not prevent ongoing cooperation between them. Indeed, there is well-established interaction between the various poles, through joint projects, conferences, seminars, co-supervision of master's and doctoral theses, among others.

Spotlight

News

Producing "green" hydrogen from water from the Meuse River? It's now possible!

Producing "green" hydrogen from water from the Meuse River? It's now possible!

At UNamur, research is not confined to laboratories. From physics to political science, robotics, biodiversity, law, AI, and health, researchers collaborate daily with numerous stakeholders in society. The goal? Transform ideas into concrete solutions to address current challenges.

Focus #2 | What if our rivers became a source of clean energy for the future?

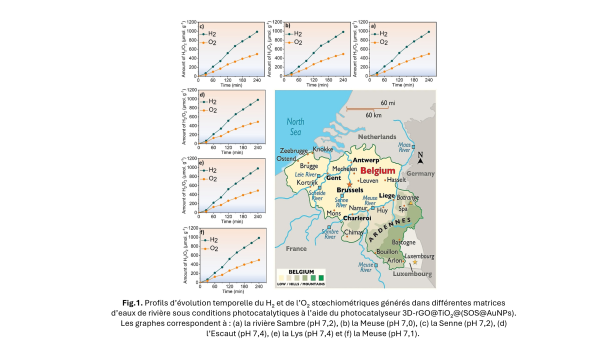

An international team of chemistry researchers, led by Dr. Laroussi Chaabane and Prof. Bao-Lian Su, has just demonstrated that it is possible to produce "green" hydrogen using natural water and sunlight. These findings have been published in the prestigious Chemical Engineering Journal.

When sunlight becomes a source of clean energy

Faced with climate change, pollution, and energy shortages, the search for alternatives to fossil fuels has become a global priority in order to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. Among the solutions being considered, green hydrogen appears to be a particularly promising energy carrier: it has a high energy density and can be produced without greenhouse gas emissions. Today, most of the world's hydrogen (around 87 million tons produced in 2020) is obtained through costly and polluting electrochemical processes, mainly used by the chemical industry or fuel cells. Hence the major interest in more sustainable methods.

Water photocatalysis: the "Holy Grail" of chemistry

Producing hydrogen and oxygen directly from water using light, a process known as photocatalysis of water, is often referred to as the "Holy Grail of chemistry" because it is so complex to master. At the University of Namur, researchers at the Laboratory of Inorganic Materials Chemistry (CMI), part of the Nanomaterials Chemistry Unit (UCNANO) and the Namur Institute of Structured Matter (NISM), have taken a decisive step forward. They have demonstrated that it is possible to use natural water, and no longer just ultrapure water, to produce green hydrogen under the action of sunlight.

The core of the process is based on an innovative photocatalyst, which acts as a kind of "chemical pair of scissors" capable of splitting water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen—an area in which the CMI laboratory has recognized expertise.

A 3D photocatalyst based on graphene and gold

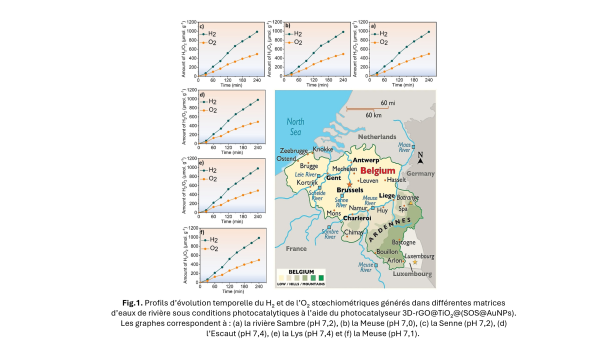

The new material developed is a three-dimensional (3D) photocatalyst based on titanium oxide, graphene, and gold nanoparticles. This 3D architecture allows for better light absorption and more efficient generation of free electrons, which are essential for triggering the water dissociation reaction. One of the main challenges lies in the use of natural water, which contains minerals, salts, and organic compounds that can disrupt the process. To address this challenge, the researchers tested their device with water from several Belgian rivers: the Meuse, the Sambre, the Scheldt, and the Yser.

A remarkable result and a first in Belgium!

The performance achieved is almost equivalent to that measured with pure water.

This is a first in Belgium, opening up concrete prospects for the sustainable use of local natural resources!

The full article, "Synergistic four physical phenomena in a 3D photocatalyst for unprecedented overall water splitting," is available in open access.

International recognition

This scientific breakthrough also earned Dr. Laroussi Chaabane the award for best poster at the 4th International Colloids Conference (San Sebastián, Spain, July 2025), highlighting the impact and originality of this work.

An international research team

- University of Namur, Faculty of Sciences, UCNANO, Laboratory of Inorganic Materials Chemistry (CMI) and Namur Institute of Structured Matter (NISM), Belgium | Principal Investigator (PI) | Professor Bao Lian SU; Postdoctoral Researcher | Dr. Laroussi Chaabane

- Institute of Organic Chemistry, Phytochemistry Center, Academy of Sciences, Bulgaria

- Department of Organic Chemistry (MSc), Loyola Academy, India

- Free University of Brussels (ULB) and Flanders Make, Department of Applied Physics and Photonics, Brussels Photonics, Belgium

- University of Quebec in Montreal (UQAM), Department of Chemistry, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

- National Institute for Scientific Research - Energy Materials Telecommunications Center (INRS-EMT), Varennes, Quebec, Canada

- Wuhan University of Technology, National Laboratory for Advanced Technologies in Materials Synthesis and Processing, China

What next?

At this stage, the study constitutes proof of concept demonstrating the feasibility of the process. It illustrates the excellence of chemical engineering and nanomaterials research at UNamur, as well as its potential for sustainable energy applications. A new study is underway to evaluate the performance of the process with seawater, a key step towards large-scale green hydrogen production.

State-of-the-art equipment

The analyses carried out were made possible thanks to the equipment available at UNamur's Physico-Chemical Characterization (PC²), Electron Microscopy, and Material Synthesis, Irradiation, and Analysis (SIAM) technology platforms. UNamur's technology platforms house state-of-the-art equipment and are accessible to the scientific community as well as to industries and companies.

The authors would like to thank the Wallonia Public Service (SPW) for its ongoing commitment to scientific research and innovation in Wallonia, enabling UNamur to develop technological solutions with a significant societal and environmental impact.

From fundamental to applied research, UNamur demonstrates every day that research is a driver of transformation. Thanks to the commitment of its researchers, the support of its partners from all walks of life, funders, industrial partners, and a solid ecosystem of valorization, UNamur actively participates in shaping a society that is open to the world, more innovative, more responsible, and more sustainable.

To go further

This article complements our publication "Research and innovation: major assets for the industrial sector" taken from the Issues section of Omalius magazine #39 (December 2025).

Delamination of sheepskin parchment: an interdisciplinary discovery published in Heritage Science

Delamination of sheepskin parchment: an interdisciplinary discovery published in Heritage Science

At UNamur, parchments are much more than objects of curiosity: they are at the heart of an interdisciplinary scientific adventure. Starting with historical sciences and conservation, the research has gradually incorporated the disciplines of physics, biology, chemistry, and archaeology. This convergence has given rise to research in heritage sciences, driving innovative projects such as Marine Appart's doctoral work, supervised by Professor Olivier Deparis. This research has now been recognized with a publication in the prestigious journal Heritage Science (Nature Publishing Group).

For several years now, heritage sciences have been experiencing a particularly significant boom. This deeply interdisciplinary field of research aims to foster dialogue between the humanities and natural sciences with a view to improving our knowledge of heritage objects, whether they be parchments, works of art, or artifacts discovered during excavations.

Manuscripts bear witness to ancestral practices and know-how, which unfortunately are poorly documented. It is still unclear why legal documents were preferably written on sheepskin parchment in England from the 13th century until 1925. Among the hypotheses put forward is the fact that sheepskin is whiter, and therefore more attractive, but above all that documents written on it were considered unforgeable due to the tendency of sheepskin to delaminate (any malicious attempt to erase the text would thus be revealed). This delamination property was exploited because it allowed the production of high-quality writing surfaces. It was also used to prepare strong repair pieces used to fill any tears that appeared during the parchment manufacturing process. Understanding why sheepskin delaminates is of interest in the context of traditional parchment preparation techniques, offering valuable insights into the interaction between animal biology, craftsmanship, and historical needs.

Delamination, what is it?

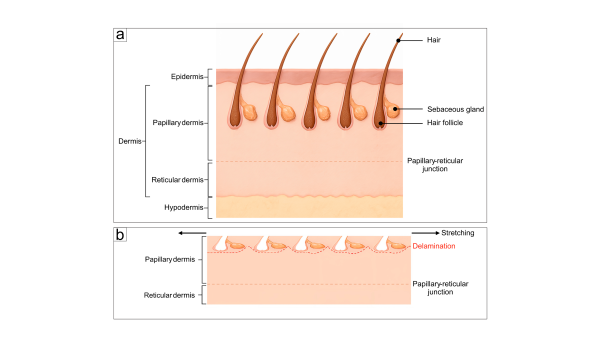

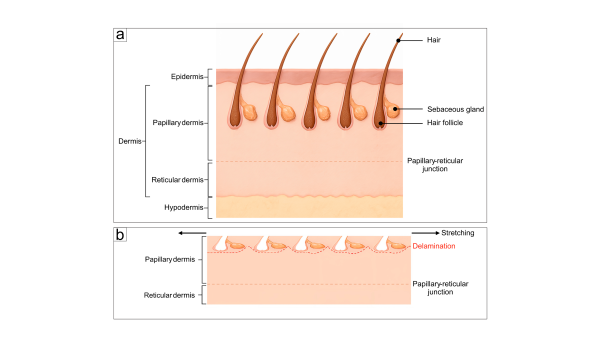

Delamination is the phenomenon whereby the inner layers of the skin separate along their interface as a result of mechanical stress. The diagram (a) below shows the structure of the skin, which consists mainly of the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis. The dermis is divided into two layers, the papillary dermis and the reticular dermis, which contain hair, hair follicles, and sebaceous glands.

During the parchment manufacturing process, a step following liming involves scraping the skin to remove the hair. This step crushes the sebaceous glands, releasing fats and creating a void where the hair was located (diagram b).

The study showed that delamination occurs within the papillary dermis itself, in this structurally weakened area, rather than at the papillary-reticular junction as previously assumed.

The unique nature of the delamination process in sheepskin is highlighted by the skin structure, which differs from that of other animals (calves, goats) used to make parchment, as it has a high fat content associated with a large number of primary and secondary hair follicles. In the study, the presence of fats was confirmed using Raman spectroscopy.

The experimental manufacture of parchment - explained in a video!

This study combines experimental archaeology and advanced analytical techniques, including scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and micro-Raman spectroscopy, to characterize the delamination process and the adhesion of repair pieces on experimentally produced sheepskin parchment. It benefits from the expertise in archaeometry, biology, chemistry, and physics of the researchers involved.

Beyond its visual and structural implications, delamination has contributed to promoting the use of sheepskin for prestigious documents, improving the surface properties of parchment. The study of the interaction between metal-gallic ink and delaminated sheepskin (wetting experiments) showed that ink diffusion and writing quality are improved, a key finding that provides insight into how surface morphology and composition influence writing performance.

An international and multidisciplinary team

At UNamur, Marine Appart, a PhD student in physics, is conducting this multidisciplinary research on the archaeometry of delamination and repairs on a sheepskin parchment under the supervision of Professor Olivier Deparis (Department of Physics, NISM Institute).

Also part of the UNamur team are:

- Professor Francesca Cecchet (expert in Raman spectroscopy), Department of Physics, NARILIS and NISM Institutes

- Professor Yves Poumay (skin specialist), Department of Medicine, NARILIS Institute

- Dr. Caroline Canon (histology specialist), Department of Medicine

- Nicolas Gros (PhD student in heritage sciences), Department of Physics, NARILIS and NISM Institutes

Other international experts

- Professor Matthew Collins (world expert in biomolecular archaeology, Department of Archaeology, The McDonald Institute, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK)

- Jiří Vnouček (curator and expert in parchment production, Preservation Department, Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen, Denmark)

- Marc Fourneau (biologist)

History of the study of parchments at UNamur

This study and the resulting article were inspired by the delamination experiments conducted in 2023 by Jiří Vnouček during a symposium in Klosterneuburg, Austria, in which Prof. Olivier Deparis participated. The symposium was organized by Professor Matthew Collins as part of the ABC and ERC Beast2Craft (B2C) projects.

But it all began in 2014, when the Pergamenum21 project, dedicated to the transdisciplinary study of parchments, was launched. Pergamenum21 is a project of the Namur Transdisciplinary Research Impulse (NaTRIP) program at the University of Namur. The project received an additional grant in 2016 from the Jean-Jacques Comhaire Fund of the King Baudouin Foundation (FRB).

The projects and events followed one after another, including:

- May 2014: a transdisciplinary seminar on parchment, the scientific techniques used to characterize this material, and historical questions at the Mauretus Plantin Library (BUMP)

- May 2017: "Autopsy of a scriptorium: the Orval parchments put to the test of bioarchaeology," a transdisciplinary research project co-financed by the University of Namur and the Jean-Jacques Comhaire Fund of the King Baudouin Foundation

- April 2019: a publication in Scientific Reports, Nature group - Jean-Jacques Comhaire Prize: discovery of an innovative technique based on measuring the light scattered by ancient parchments. This technique makes it possible to characterize, in a non-invasive way, the nature of the skins used in the Middle Ages to make parchments

- September 2020: a residential workshop on making parchment from animal skins at the Domaine d'Haugimont – a first in Belgium

- July 2022: a new project on parchment bindings for the restoration workshop at the Moretus Plantin University Library (BUMP) thanks to the Jean-Jacques Comhaire Fund of the King Baudouin Foundation.

- September 2024: a residential symposium-workshop at the Domaine d'Haugimont on the theme of the physicochemistry of parchment and inks using experimental and historical approaches

Overall, the work of Marine Appart and her colleagues clarifies the structural and material factors that make sheepskin parchment susceptible to delamination and offers new insights into the surface properties of this ancient writing material. UNamur is now establishing itself as a major player in parchment research.

Professor Olivier Deparis, along with several of the researchers involved in this research, are also working on the ARC PHOENIX project. This project aims to renew our understanding of medieval parchments and ancient coins. Artificial intelligence is used to analyze the data generated by the characterization of materials. This joint study will address issues related to the production chain and the use of these objects and materials in past societies.

10 years of UNamur - STÛV collaboration: a lever for innovation, attractiveness and excellence

10 years of UNamur - STÛV collaboration: a lever for innovation, attractiveness and excellence

The University of Namur and STÛV, a Namur-based company specializing in wood and pellet heating solutions, are celebrating ten years of fruitful collaboration. This partnership illustrates the importance of synergies between academia and industry to improve competitiveness and meet environmental challenges.

For over 30 years, UNamur, via its Chemistry of Inorganic Materials Laboratory (CMI) headed by Professor Bao-Lian Su, has excelled in fundamental research into catalytic solutions capable of "cleaning" air and water. In 2014, STÛV approached this expertise to design a sustainable, low-cost smoke purification system for wood-burning stoves, in anticipation of the tightening of European standards.

The R-PUR project: a decisive first step

From this meeting was born the R-PUR applied research project, funded by the Walloon Region and the European Union as part of the Beware program, led by Tarek Barakat (UNamur - CMI). Between 2014 and 2017, an innovative catalytic filter was thus developed within the laboratory, in close collaboration with STÛV.

From 2018 to 2024, the technologies patented by STÛV and UNamur and the pollutant measurement equipment were gradually transferred to STÛV, at the same time as Win4Spin-off and Proof of Concept funding enabled technological and commercial maturities to be increased to meet market needs. These steps led to laying the foundations for a new Business Unit at STÛV, with the hiring of Tarek Barakat as Project Manager, and raising investments to produce the catalytic filters.

What about tomorrow? Towards zero-emission combustion

The UNamur-STÛV collaboration continues today with the Win4Doc (doctorate in business) DeCOVskite project, led by PhD student Louis Garin (UNamur - CMI) and supervised by Tarek Barakat. Objectives:

- Develop a second generation of catalysts to completely reduce fine particle emissions.

- Limit the use of precious metals.

- Sustain biomass combustion and make STÛV the world leader in zero-emission stoves.

A winning partnership for the region

This collaboration has enabled:

- The acquisition and transfer of know-how and equipment between UNamur and STÛV to validate results under industrial conditions.

- The organization of multidisciplinary workshops, such as the one on October 14, promoting the sharing of expertise around biomass combustion and sustainable development.

Success-Story: interviews and testimonials

At the end of October, members of UNamur and STÛV came together to take part in a workshop organized by UNamur's Research Administration and STÛV. The aim? To highlight the benefits of collaborative research between companies and universities on subjects ranging from energy, the environment, profitability, ethics and regulation to sustainable development. The two partners discussed their collaboration, expertise and development prospects.

Discover the details of this success story in this video :

35 years between two accelerators - Serge Mathot's journey, or the art of welding history to physics

35 years between two accelerators - Serge Mathot's journey, or the art of welding history to physics

One foot in the past, the other in the future. From Etruscan granulation to PIXE analysis, Serge Mathot has built a unique career, between scientific heritage and particle accelerators. Portrait of a passionate alumnus at the crossroads of disciplines.

What prompted you to undertake your studies and then your doctorate in physics?

I was fascinated by the research field of one of my professors, Guy Demortier. He was working on the characterization of antique jewelry. He had found a way to differentiate by PIXE (Proton Induced X-ray Emission) analysis between antique and modern brazes that contained Cadmium, the presence of this element in antique jewelry being controversial at the time. He was interested in ancient soldering methods in general, and the granulation technique in particular. He studied them at the Laboratoire d'Analyses par Réaction Nucléaires (LARN). Brazing is an assembly operation involving the fusion of a filler metal (e.g. copper- or silver-based) without melting the base metal. This phenomenon allows a liquid metal to penetrate first by capillary action and then by diffusion at the interface of the metals to be joined, making the junction permanent after solidification. Among the jewels of antiquity, we find brazes made with incredible precision, the ancient techniques are fascinating.

Studying antique jewelry? Not what you'd expect in physics.

In fact, this was one of Namur's fields of research at the time: heritage sciences. Professor Demortier was conducting studies on a variety of jewels, but those made by the Etruscans using the so-called granulation technique, which first appeared in Eturia in the 8th century BC, are particularly incredible. It consists of depositing hundreds of tiny gold granules, up to two-tenths of a millimeter in diameter, on the surface to be decorated, and then soldering them onto the jewel without altering its fineness. So I also trained in brazing techniques and physical metallurgy.

The characterization of jewelry using LARN's particle accelerator, which enables non-destructive analysis, yields valuable information for heritage science.

This is, moreover, a current area of collaboration between the Department of Physics and the Department of History at UNamur (NDLR: notably through the ARC Phoenix project).

How did that help you land a job at CERN?

I applied for a position as a physicist at CERN in the field of vacuum and thin films, but was invited for the position of head of the vacuum brazing department. This department is very important for CERN as it studies methods for assembling particularly delicate and precise parts for accelerators. It also manufactures prototypes and often one-off parts. Broadly speaking, vacuum brazing is the same technique as the one we study at Namur, except that it is carried out in a vacuum chamber. This means no oxidation, perfect wetting of the brazing alloys on the parts to be assembled, and very precise temperature control to obtain very precise assemblies (we're talking microns!). I'd never heard of vacuum brazing, but my experience of Etruscan brazing, metallurgy and my background in applied physics as taught at Namur were of particular interest to the selection committee. They hired me right away!

Tell us about CERN and the projects that keep you busy.

CERN is primarily known for hosting particle accelerators, including the famous LHC (Large Hadron Collider), a 27 km circumference accelerator buried some 100 m underground, which accelerates particles to 99.9999991% of the speed of light! CERN's research focuses on technology and innovation in many fields: nuclear physics, cosmic rays and cloud formation, antimatter research, the search for rare phenomena (such as the Higgs boson) and a contribution to neutrino research. It is also the birthplace of the World Wide Web (WWW). There are also projects in healthcare, medicine and partnerships with industry.

Nuclear physics at CERN is very different from what we do at UNamur with the ALTAÏS accelerator. But my training in applied physics (namuroise) has enabled me to integrate seamlessly into various research projects.

For my part, in addition to developing vacuum brazing methods, a field in which I've worked for over 20 years, I've worked a lot in parallel for the CLOUD experiment. For over 10 years, and until recently, I was its Technical Coordinator. CLOUD is a small but fascinating experiment at CERN which studies cloud formation and uses a particle beam to reproduce atomic bombardment in the laboratory in the manner of galactic radiation in our atmosphere. Using an ultra-clean 26 m³ cloud chamber, precise gas injection systems, electric fields, UV light systems and multiple detectors, we reproduce and study the Earth's atmosphere to understand whether galactic rays can indeed influence climate. This experiment calls on various fields of applied physics, and my background at UNamur has helped me once again.

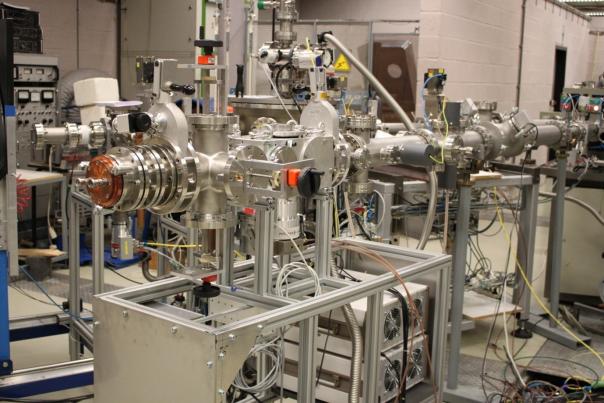

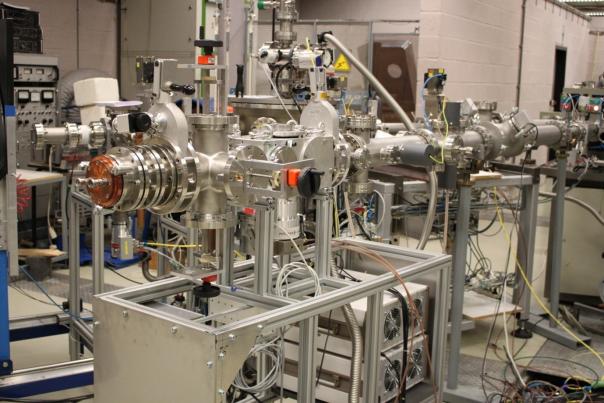

I was also responsible for CERN's MACHINA project -Movable Accelerator for Cultural Heritage In situ Non-destructive Analysis - carried out in collaboration with the Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (INFN), Florence section - Italy. Together, we have created the first portable proton accelerator for in-situ, non-destructive analysis in heritage science. MACHINA is soon to be used at the OPD (Opificio delle Pietre Dure), one of the oldest and most prestigious art restoration centers, also in Florence. The accelerator is also destined to travel to other museums or restoration centers.

Currently, I'm in charge of the ELISA (Experimental LInac for Surface Analysis) project. With ELISA, we're running a real proton accelerator for the first time in a place open to the public: the Science Gateway (SGW), CERN's new permanent exhibition center

ELISA uses the same accelerator cavity as MACHINA. The public can observe a proton beam extracted just a few centimetres from their eyes. Demonstrations are organized to show various physical phenomena, such as light production in gases or beam deflection with dipoles or quadrupoles, for example. The PIXE analysis method is also presented. ELISA is also a high-performance accelerator that we use for research projects in the field of heritage and others such as thin films, which are used extensively at CERN. The special feature is that the scientists who come to work with us do so in front of the public!

Do you have a story to tell?

I remember that in 1989, I finished typing my report for my IRSIA fellowship in the middle of the night, the day before the deadline. It had to be in by midnight the next day. There were very few computers back then, so I typed my report at the last minute on one of the secretaries' Macs. One false move and pow! all my data was gone - big panic! The next day, the secretary helped me restore my file, we printed out the document and I dropped it straight into the mailbox in Brussels, where I arrived after 11pm, in extremis, because at midnight, someone had come to close the mailbox. Fortunately, technology has come a long way since then...

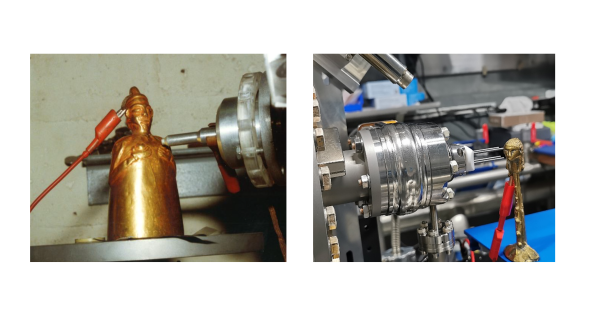

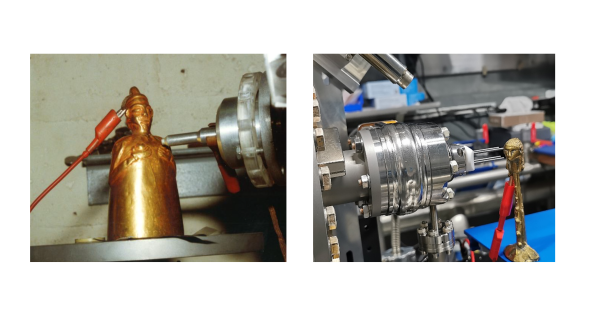

And I can't resist sharing two images 35 years apart!

To the left, a Gold statuette (Egypt), c. 2000 BC, analyzed at LARN - UNamur (photo 1990) and to the right, a copy (in Brass) of the Dame de Brassempouy, analyzed with ELISA - CERN (2025).

The "photographer" is the same, so we've come full circle...

The proximity between teaching and research inspires and questions. This enables graduate students to move into multiple areas of working life.

Come and study in Namur!

Serge Mathot (May 2025) - Interview by Karin Derochette

Further information

- The CERN accelerators complex

- The Science Portal, CERN's public education and communication center

- Newsroom - June 2025 | The Departement of physics hosts a delegation from CERN

- Newsroom and Omalius Alumni article - September 2022 | François Briard

CERN - the science portal

This article is taken from the "Alumni" section of Omalius magazine #38 (September 2025).

Producing "green" hydrogen from water from the Meuse River? It's now possible!

Producing "green" hydrogen from water from the Meuse River? It's now possible!

At UNamur, research is not confined to laboratories. From physics to political science, robotics, biodiversity, law, AI, and health, researchers collaborate daily with numerous stakeholders in society. The goal? Transform ideas into concrete solutions to address current challenges.

Focus #2 | What if our rivers became a source of clean energy for the future?

An international team of chemistry researchers, led by Dr. Laroussi Chaabane and Prof. Bao-Lian Su, has just demonstrated that it is possible to produce "green" hydrogen using natural water and sunlight. These findings have been published in the prestigious Chemical Engineering Journal.

When sunlight becomes a source of clean energy

Faced with climate change, pollution, and energy shortages, the search for alternatives to fossil fuels has become a global priority in order to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. Among the solutions being considered, green hydrogen appears to be a particularly promising energy carrier: it has a high energy density and can be produced without greenhouse gas emissions. Today, most of the world's hydrogen (around 87 million tons produced in 2020) is obtained through costly and polluting electrochemical processes, mainly used by the chemical industry or fuel cells. Hence the major interest in more sustainable methods.

Water photocatalysis: the "Holy Grail" of chemistry

Producing hydrogen and oxygen directly from water using light, a process known as photocatalysis of water, is often referred to as the "Holy Grail of chemistry" because it is so complex to master. At the University of Namur, researchers at the Laboratory of Inorganic Materials Chemistry (CMI), part of the Nanomaterials Chemistry Unit (UCNANO) and the Namur Institute of Structured Matter (NISM), have taken a decisive step forward. They have demonstrated that it is possible to use natural water, and no longer just ultrapure water, to produce green hydrogen under the action of sunlight.

The core of the process is based on an innovative photocatalyst, which acts as a kind of "chemical pair of scissors" capable of splitting water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen—an area in which the CMI laboratory has recognized expertise.

A 3D photocatalyst based on graphene and gold

The new material developed is a three-dimensional (3D) photocatalyst based on titanium oxide, graphene, and gold nanoparticles. This 3D architecture allows for better light absorption and more efficient generation of free electrons, which are essential for triggering the water dissociation reaction. One of the main challenges lies in the use of natural water, which contains minerals, salts, and organic compounds that can disrupt the process. To address this challenge, the researchers tested their device with water from several Belgian rivers: the Meuse, the Sambre, the Scheldt, and the Yser.

A remarkable result and a first in Belgium!

The performance achieved is almost equivalent to that measured with pure water.

This is a first in Belgium, opening up concrete prospects for the sustainable use of local natural resources!

The full article, "Synergistic four physical phenomena in a 3D photocatalyst for unprecedented overall water splitting," is available in open access.

International recognition

This scientific breakthrough also earned Dr. Laroussi Chaabane the award for best poster at the 4th International Colloids Conference (San Sebastián, Spain, July 2025), highlighting the impact and originality of this work.

An international research team

- University of Namur, Faculty of Sciences, UCNANO, Laboratory of Inorganic Materials Chemistry (CMI) and Namur Institute of Structured Matter (NISM), Belgium | Principal Investigator (PI) | Professor Bao Lian SU; Postdoctoral Researcher | Dr. Laroussi Chaabane

- Institute of Organic Chemistry, Phytochemistry Center, Academy of Sciences, Bulgaria

- Department of Organic Chemistry (MSc), Loyola Academy, India

- Free University of Brussels (ULB) and Flanders Make, Department of Applied Physics and Photonics, Brussels Photonics, Belgium

- University of Quebec in Montreal (UQAM), Department of Chemistry, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

- National Institute for Scientific Research - Energy Materials Telecommunications Center (INRS-EMT), Varennes, Quebec, Canada

- Wuhan University of Technology, National Laboratory for Advanced Technologies in Materials Synthesis and Processing, China

What next?

At this stage, the study constitutes proof of concept demonstrating the feasibility of the process. It illustrates the excellence of chemical engineering and nanomaterials research at UNamur, as well as its potential for sustainable energy applications. A new study is underway to evaluate the performance of the process with seawater, a key step towards large-scale green hydrogen production.

State-of-the-art equipment

The analyses carried out were made possible thanks to the equipment available at UNamur's Physico-Chemical Characterization (PC²), Electron Microscopy, and Material Synthesis, Irradiation, and Analysis (SIAM) technology platforms. UNamur's technology platforms house state-of-the-art equipment and are accessible to the scientific community as well as to industries and companies.

The authors would like to thank the Wallonia Public Service (SPW) for its ongoing commitment to scientific research and innovation in Wallonia, enabling UNamur to develop technological solutions with a significant societal and environmental impact.

From fundamental to applied research, UNamur demonstrates every day that research is a driver of transformation. Thanks to the commitment of its researchers, the support of its partners from all walks of life, funders, industrial partners, and a solid ecosystem of valorization, UNamur actively participates in shaping a society that is open to the world, more innovative, more responsible, and more sustainable.

To go further

This article complements our publication "Research and innovation: major assets for the industrial sector" taken from the Issues section of Omalius magazine #39 (December 2025).

Delamination of sheepskin parchment: an interdisciplinary discovery published in Heritage Science

Delamination of sheepskin parchment: an interdisciplinary discovery published in Heritage Science

At UNamur, parchments are much more than objects of curiosity: they are at the heart of an interdisciplinary scientific adventure. Starting with historical sciences and conservation, the research has gradually incorporated the disciplines of physics, biology, chemistry, and archaeology. This convergence has given rise to research in heritage sciences, driving innovative projects such as Marine Appart's doctoral work, supervised by Professor Olivier Deparis. This research has now been recognized with a publication in the prestigious journal Heritage Science (Nature Publishing Group).

For several years now, heritage sciences have been experiencing a particularly significant boom. This deeply interdisciplinary field of research aims to foster dialogue between the humanities and natural sciences with a view to improving our knowledge of heritage objects, whether they be parchments, works of art, or artifacts discovered during excavations.

Manuscripts bear witness to ancestral practices and know-how, which unfortunately are poorly documented. It is still unclear why legal documents were preferably written on sheepskin parchment in England from the 13th century until 1925. Among the hypotheses put forward is the fact that sheepskin is whiter, and therefore more attractive, but above all that documents written on it were considered unforgeable due to the tendency of sheepskin to delaminate (any malicious attempt to erase the text would thus be revealed). This delamination property was exploited because it allowed the production of high-quality writing surfaces. It was also used to prepare strong repair pieces used to fill any tears that appeared during the parchment manufacturing process. Understanding why sheepskin delaminates is of interest in the context of traditional parchment preparation techniques, offering valuable insights into the interaction between animal biology, craftsmanship, and historical needs.

Delamination, what is it?

Delamination is the phenomenon whereby the inner layers of the skin separate along their interface as a result of mechanical stress. The diagram (a) below shows the structure of the skin, which consists mainly of the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis. The dermis is divided into two layers, the papillary dermis and the reticular dermis, which contain hair, hair follicles, and sebaceous glands.

During the parchment manufacturing process, a step following liming involves scraping the skin to remove the hair. This step crushes the sebaceous glands, releasing fats and creating a void where the hair was located (diagram b).

The study showed that delamination occurs within the papillary dermis itself, in this structurally weakened area, rather than at the papillary-reticular junction as previously assumed.

The unique nature of the delamination process in sheepskin is highlighted by the skin structure, which differs from that of other animals (calves, goats) used to make parchment, as it has a high fat content associated with a large number of primary and secondary hair follicles. In the study, the presence of fats was confirmed using Raman spectroscopy.

The experimental manufacture of parchment - explained in a video!

This study combines experimental archaeology and advanced analytical techniques, including scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and micro-Raman spectroscopy, to characterize the delamination process and the adhesion of repair pieces on experimentally produced sheepskin parchment. It benefits from the expertise in archaeometry, biology, chemistry, and physics of the researchers involved.

Beyond its visual and structural implications, delamination has contributed to promoting the use of sheepskin for prestigious documents, improving the surface properties of parchment. The study of the interaction between metal-gallic ink and delaminated sheepskin (wetting experiments) showed that ink diffusion and writing quality are improved, a key finding that provides insight into how surface morphology and composition influence writing performance.

An international and multidisciplinary team

At UNamur, Marine Appart, a PhD student in physics, is conducting this multidisciplinary research on the archaeometry of delamination and repairs on a sheepskin parchment under the supervision of Professor Olivier Deparis (Department of Physics, NISM Institute).

Also part of the UNamur team are:

- Professor Francesca Cecchet (expert in Raman spectroscopy), Department of Physics, NARILIS and NISM Institutes

- Professor Yves Poumay (skin specialist), Department of Medicine, NARILIS Institute

- Dr. Caroline Canon (histology specialist), Department of Medicine

- Nicolas Gros (PhD student in heritage sciences), Department of Physics, NARILIS and NISM Institutes

Other international experts

- Professor Matthew Collins (world expert in biomolecular archaeology, Department of Archaeology, The McDonald Institute, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK)

- Jiří Vnouček (curator and expert in parchment production, Preservation Department, Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen, Denmark)

- Marc Fourneau (biologist)

History of the study of parchments at UNamur

This study and the resulting article were inspired by the delamination experiments conducted in 2023 by Jiří Vnouček during a symposium in Klosterneuburg, Austria, in which Prof. Olivier Deparis participated. The symposium was organized by Professor Matthew Collins as part of the ABC and ERC Beast2Craft (B2C) projects.

But it all began in 2014, when the Pergamenum21 project, dedicated to the transdisciplinary study of parchments, was launched. Pergamenum21 is a project of the Namur Transdisciplinary Research Impulse (NaTRIP) program at the University of Namur. The project received an additional grant in 2016 from the Jean-Jacques Comhaire Fund of the King Baudouin Foundation (FRB).

The projects and events followed one after another, including:

- May 2014: a transdisciplinary seminar on parchment, the scientific techniques used to characterize this material, and historical questions at the Mauretus Plantin Library (BUMP)

- May 2017: "Autopsy of a scriptorium: the Orval parchments put to the test of bioarchaeology," a transdisciplinary research project co-financed by the University of Namur and the Jean-Jacques Comhaire Fund of the King Baudouin Foundation

- April 2019: a publication in Scientific Reports, Nature group - Jean-Jacques Comhaire Prize: discovery of an innovative technique based on measuring the light scattered by ancient parchments. This technique makes it possible to characterize, in a non-invasive way, the nature of the skins used in the Middle Ages to make parchments

- September 2020: a residential workshop on making parchment from animal skins at the Domaine d'Haugimont – a first in Belgium

- July 2022: a new project on parchment bindings for the restoration workshop at the Moretus Plantin University Library (BUMP) thanks to the Jean-Jacques Comhaire Fund of the King Baudouin Foundation.

- September 2024: a residential symposium-workshop at the Domaine d'Haugimont on the theme of the physicochemistry of parchment and inks using experimental and historical approaches

Overall, the work of Marine Appart and her colleagues clarifies the structural and material factors that make sheepskin parchment susceptible to delamination and offers new insights into the surface properties of this ancient writing material. UNamur is now establishing itself as a major player in parchment research.

Professor Olivier Deparis, along with several of the researchers involved in this research, are also working on the ARC PHOENIX project. This project aims to renew our understanding of medieval parchments and ancient coins. Artificial intelligence is used to analyze the data generated by the characterization of materials. This joint study will address issues related to the production chain and the use of these objects and materials in past societies.

10 years of UNamur - STÛV collaboration: a lever for innovation, attractiveness and excellence

10 years of UNamur - STÛV collaboration: a lever for innovation, attractiveness and excellence

The University of Namur and STÛV, a Namur-based company specializing in wood and pellet heating solutions, are celebrating ten years of fruitful collaboration. This partnership illustrates the importance of synergies between academia and industry to improve competitiveness and meet environmental challenges.

For over 30 years, UNamur, via its Chemistry of Inorganic Materials Laboratory (CMI) headed by Professor Bao-Lian Su, has excelled in fundamental research into catalytic solutions capable of "cleaning" air and water. In 2014, STÛV approached this expertise to design a sustainable, low-cost smoke purification system for wood-burning stoves, in anticipation of the tightening of European standards.

The R-PUR project: a decisive first step

From this meeting was born the R-PUR applied research project, funded by the Walloon Region and the European Union as part of the Beware program, led by Tarek Barakat (UNamur - CMI). Between 2014 and 2017, an innovative catalytic filter was thus developed within the laboratory, in close collaboration with STÛV.

From 2018 to 2024, the technologies patented by STÛV and UNamur and the pollutant measurement equipment were gradually transferred to STÛV, at the same time as Win4Spin-off and Proof of Concept funding enabled technological and commercial maturities to be increased to meet market needs. These steps led to laying the foundations for a new Business Unit at STÛV, with the hiring of Tarek Barakat as Project Manager, and raising investments to produce the catalytic filters.

What about tomorrow? Towards zero-emission combustion

The UNamur-STÛV collaboration continues today with the Win4Doc (doctorate in business) DeCOVskite project, led by PhD student Louis Garin (UNamur - CMI) and supervised by Tarek Barakat. Objectives:

- Develop a second generation of catalysts to completely reduce fine particle emissions.

- Limit the use of precious metals.

- Sustain biomass combustion and make STÛV the world leader in zero-emission stoves.

A winning partnership for the region

This collaboration has enabled:

- The acquisition and transfer of know-how and equipment between UNamur and STÛV to validate results under industrial conditions.

- The organization of multidisciplinary workshops, such as the one on October 14, promoting the sharing of expertise around biomass combustion and sustainable development.

Success-Story: interviews and testimonials

At the end of October, members of UNamur and STÛV came together to take part in a workshop organized by UNamur's Research Administration and STÛV. The aim? To highlight the benefits of collaborative research between companies and universities on subjects ranging from energy, the environment, profitability, ethics and regulation to sustainable development. The two partners discussed their collaboration, expertise and development prospects.

Discover the details of this success story in this video :

35 years between two accelerators - Serge Mathot's journey, or the art of welding history to physics

35 years between two accelerators - Serge Mathot's journey, or the art of welding history to physics

One foot in the past, the other in the future. From Etruscan granulation to PIXE analysis, Serge Mathot has built a unique career, between scientific heritage and particle accelerators. Portrait of a passionate alumnus at the crossroads of disciplines.

What prompted you to undertake your studies and then your doctorate in physics?

I was fascinated by the research field of one of my professors, Guy Demortier. He was working on the characterization of antique jewelry. He had found a way to differentiate by PIXE (Proton Induced X-ray Emission) analysis between antique and modern brazes that contained Cadmium, the presence of this element in antique jewelry being controversial at the time. He was interested in ancient soldering methods in general, and the granulation technique in particular. He studied them at the Laboratoire d'Analyses par Réaction Nucléaires (LARN). Brazing is an assembly operation involving the fusion of a filler metal (e.g. copper- or silver-based) without melting the base metal. This phenomenon allows a liquid metal to penetrate first by capillary action and then by diffusion at the interface of the metals to be joined, making the junction permanent after solidification. Among the jewels of antiquity, we find brazes made with incredible precision, the ancient techniques are fascinating.

Studying antique jewelry? Not what you'd expect in physics.

In fact, this was one of Namur's fields of research at the time: heritage sciences. Professor Demortier was conducting studies on a variety of jewels, but those made by the Etruscans using the so-called granulation technique, which first appeared in Eturia in the 8th century BC, are particularly incredible. It consists of depositing hundreds of tiny gold granules, up to two-tenths of a millimeter in diameter, on the surface to be decorated, and then soldering them onto the jewel without altering its fineness. So I also trained in brazing techniques and physical metallurgy.

The characterization of jewelry using LARN's particle accelerator, which enables non-destructive analysis, yields valuable information for heritage science.

This is, moreover, a current area of collaboration between the Department of Physics and the Department of History at UNamur (NDLR: notably through the ARC Phoenix project).

How did that help you land a job at CERN?

I applied for a position as a physicist at CERN in the field of vacuum and thin films, but was invited for the position of head of the vacuum brazing department. This department is very important for CERN as it studies methods for assembling particularly delicate and precise parts for accelerators. It also manufactures prototypes and often one-off parts. Broadly speaking, vacuum brazing is the same technique as the one we study at Namur, except that it is carried out in a vacuum chamber. This means no oxidation, perfect wetting of the brazing alloys on the parts to be assembled, and very precise temperature control to obtain very precise assemblies (we're talking microns!). I'd never heard of vacuum brazing, but my experience of Etruscan brazing, metallurgy and my background in applied physics as taught at Namur were of particular interest to the selection committee. They hired me right away!

Tell us about CERN and the projects that keep you busy.

CERN is primarily known for hosting particle accelerators, including the famous LHC (Large Hadron Collider), a 27 km circumference accelerator buried some 100 m underground, which accelerates particles to 99.9999991% of the speed of light! CERN's research focuses on technology and innovation in many fields: nuclear physics, cosmic rays and cloud formation, antimatter research, the search for rare phenomena (such as the Higgs boson) and a contribution to neutrino research. It is also the birthplace of the World Wide Web (WWW). There are also projects in healthcare, medicine and partnerships with industry.

Nuclear physics at CERN is very different from what we do at UNamur with the ALTAÏS accelerator. But my training in applied physics (namuroise) has enabled me to integrate seamlessly into various research projects.

For my part, in addition to developing vacuum brazing methods, a field in which I've worked for over 20 years, I've worked a lot in parallel for the CLOUD experiment. For over 10 years, and until recently, I was its Technical Coordinator. CLOUD is a small but fascinating experiment at CERN which studies cloud formation and uses a particle beam to reproduce atomic bombardment in the laboratory in the manner of galactic radiation in our atmosphere. Using an ultra-clean 26 m³ cloud chamber, precise gas injection systems, electric fields, UV light systems and multiple detectors, we reproduce and study the Earth's atmosphere to understand whether galactic rays can indeed influence climate. This experiment calls on various fields of applied physics, and my background at UNamur has helped me once again.

I was also responsible for CERN's MACHINA project -Movable Accelerator for Cultural Heritage In situ Non-destructive Analysis - carried out in collaboration with the Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (INFN), Florence section - Italy. Together, we have created the first portable proton accelerator for in-situ, non-destructive analysis in heritage science. MACHINA is soon to be used at the OPD (Opificio delle Pietre Dure), one of the oldest and most prestigious art restoration centers, also in Florence. The accelerator is also destined to travel to other museums or restoration centers.

Currently, I'm in charge of the ELISA (Experimental LInac for Surface Analysis) project. With ELISA, we're running a real proton accelerator for the first time in a place open to the public: the Science Gateway (SGW), CERN's new permanent exhibition center

ELISA uses the same accelerator cavity as MACHINA. The public can observe a proton beam extracted just a few centimetres from their eyes. Demonstrations are organized to show various physical phenomena, such as light production in gases or beam deflection with dipoles or quadrupoles, for example. The PIXE analysis method is also presented. ELISA is also a high-performance accelerator that we use for research projects in the field of heritage and others such as thin films, which are used extensively at CERN. The special feature is that the scientists who come to work with us do so in front of the public!

Do you have a story to tell?

I remember that in 1989, I finished typing my report for my IRSIA fellowship in the middle of the night, the day before the deadline. It had to be in by midnight the next day. There were very few computers back then, so I typed my report at the last minute on one of the secretaries' Macs. One false move and pow! all my data was gone - big panic! The next day, the secretary helped me restore my file, we printed out the document and I dropped it straight into the mailbox in Brussels, where I arrived after 11pm, in extremis, because at midnight, someone had come to close the mailbox. Fortunately, technology has come a long way since then...

And I can't resist sharing two images 35 years apart!

To the left, a Gold statuette (Egypt), c. 2000 BC, analyzed at LARN - UNamur (photo 1990) and to the right, a copy (in Brass) of the Dame de Brassempouy, analyzed with ELISA - CERN (2025).

The "photographer" is the same, so we've come full circle...

The proximity between teaching and research inspires and questions. This enables graduate students to move into multiple areas of working life.

Come and study in Namur!

Serge Mathot (May 2025) - Interview by Karin Derochette

Further information

- The CERN accelerators complex

- The Science Portal, CERN's public education and communication center

- Newsroom - June 2025 | The Departement of physics hosts a delegation from CERN

- Newsroom and Omalius Alumni article - September 2022 | François Briard

CERN - the science portal

This article is taken from the "Alumni" section of Omalius magazine #38 (September 2025).

Agenda

15th International Conference on Electroluminescence and Optoelectronic Devices (ICEL 2026)

ICEL is recognized as a leading research conference in the field of organic electroluminescence and devices. This event has been organized, generally every two years, since its inception in Fukuoka, Japan, in 1997, by Professor Tetsuo Tsutsui.

In 2026, the Department of Chemistry and Professors Yoann Olivier and Benoît Champagne are pleased to host this event at the University of Namur.

In line with its predecessors, ICEL 2026 will provide an excellent opportunity for the intellectual and social exchanges that keep our community closely connected. It will bring together participants from all over the world involved in the research, development, and manufacturing of emissive materials. A wide array of subjects will be explored, offering a comprehensive perspective on contemporary advances in these fields. We extend a warm invitation for the dissemination of recent breakthroughs in related topics, with a particular emphasis on fostering the active participation of young and motivated researchers.

We especially expect to cover the following topics:

- Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence emitters

- Radical emitters

- Organometallic complexes

- Perovskites

- Lasing

- Circularly polarized luminescence

- Light emission from exciplexes

- Green- and biophotonics

- Computational modeling of light-emitting materials

All practical information (registration, abstract submission, and accommodation) is available on the ICEL2026 website.

IBAF Conference 2026

Sixteen years after hosting the 2010 edition, UNamur is delighted to revive this scientific tradition and welcome the 11th edition of the Rencontres Ion Beam Applications Francophones (IBAF). This edition will be organized by scientists from the UNamur Physics Department who are active in the fields of materials science, biophysics, and interdisciplinary applications of ion beams.

The IBAF Meetings have been organized since 2003, every two years since 2008, by the Ion Beams Division of the French Vacuum Society (SFV), the oldest national vacuum society in the world, which celebrated its 80th anniversary in 2025.

As in previous editions, IBAF 2026 will offer a rich and varied program with guest lectures, oral and poster presentations, and technical sessions. All this will be complemented by an industrial presence to promote exchanges between research and innovation.

The conference will cover a wide range of topics, from ion beam instruments and techniques to the physics of ion-matter interactions, including the analysis and modification of materials, applications in the life sciences, earth and environmental sciences, and heritage sciences.