The beginnings of mobility and scientific networks in the Belle Époque

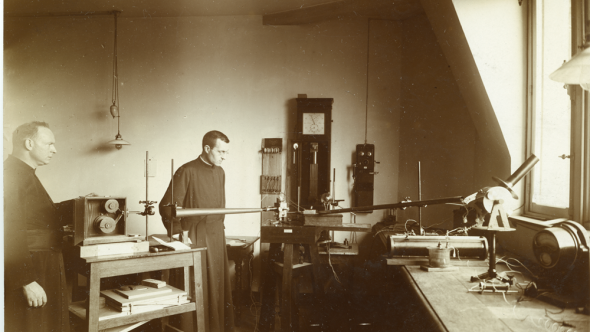

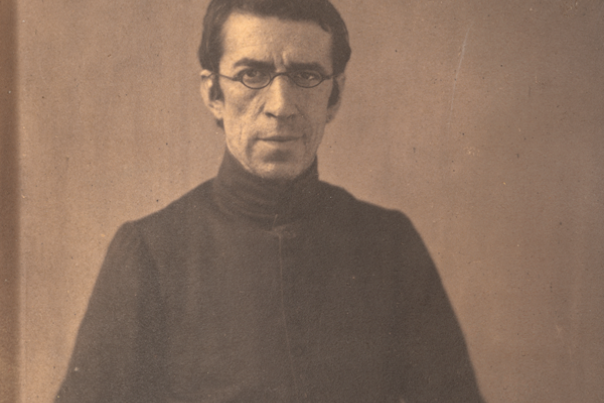

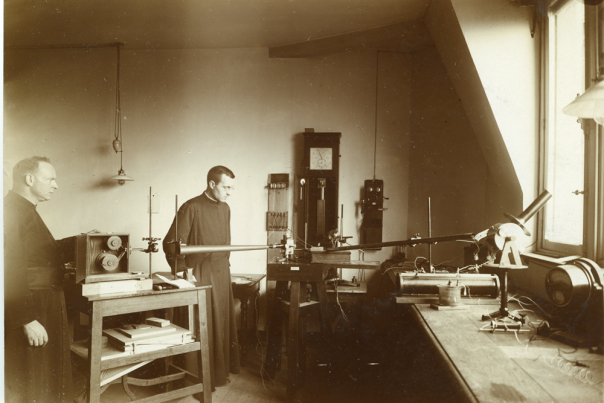

The Moretus Plantin University Library (BUMP) holds numerous archives that bear witness to UNamur's past. They document the emergence of scientific research in the faculties and, in particular, the rise of mobility and international networks at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, driven by several professors. Correspondence, photographs, and personal notes shed light on the activities of these pioneering figures.