Omalius: Your latest novel, And That's How We'll Live (Belfond, 2023), is set in 2045. The country you grew up in no longer exists: a new Civil War has left two enemy states face to face, the United Republic, which unites the East and West coasts, and the Confederacy of Central States, a country governed by the most rigorist Christianity. Is this dark, breathless, intensely political novel as dystopian as you might think?

Douglas Kennedy: Above all, it's a very topical novel. In any case, it's not science fiction, but I'd say it's a novel of anticipation, which is different. Why did I choose to set the book in 2045? Because it's 100 years after the Second World War, and I was born 10 years after the Second World War. So I grew up with the idea that being American was the greatest gift in the world: Americans had saved the world, we were the symbol of victory and freedom. But we were also extremely isolated, closed in on ourselves. I decided to set the book in 2045 because in the USA, we've been in a cultural war since the late 60s, dividing Republicans and Democrats, with the minority ruling much of the time. I wanted to write about a world without freedom, divided into two categories with their own limits, their own drift. Ultimately, this novel is a form of warning: we have to get out of this logic.

O. : In And That's How We'll Live, technology is omnipresent, managing every aspect of people's lives, for better or for worse. What is your perception of this technological world?

D. K. : Today, we're living through a technological revolution where we have the unfortunate impression that we no longer have a private life. With the omnipresence of technology, we know everything about ourselves, everything is accessible. But everyone has their secrets. The situation is similar to that of the 1930s, when totalitarianism gradually took hold. We are also on the eve of a new presidential election in the United States, marked by the rise of extremes. This is a pivotal time when there is still time to act. We still have the choice to change. Through my novels, I issue warnings to raise awareness and break out of these totalitarian patterns. I have no ambition to moralize my readers, but I do try to alert them to the evolution of our society, to the reality we find ourselves in, by projecting them into a future world.

O. : Each of your novels is characterized by a tension between the intimate (couples in crisis, the family unit, individual paths) and the social. The world of work, for example, has always played a major role in your novels. What's your secret for so skilfully crossing the boundaries between individual and collective stories?

D. K. : For me, it all starts with the family: it's always been true. When you delve into Greek mythology, the family is already at the heart of the whole story. But show me a stable family. Family dynamics are difficult. I myself grew up in a very difficult family, but thanks to that I'm a novelist! The family provides a lot of "material" for the writer. The theme of the couple is also at the heart of our lives and therefore of my novels. It's difficult to create and maintain a couple. Every love story begins with a completely clear road: everything is possible and peaceful. Then, after a while, two trucks arrive, full of suitcases. And you have to see if you can keep up with the other person's suitcases. I've found a wide readership not by tackling intellectual themes, but by proposing very direct questions connected to the daily lives of each and every one of us. I'm passionate about other people's lives, and it's my favorite subject.

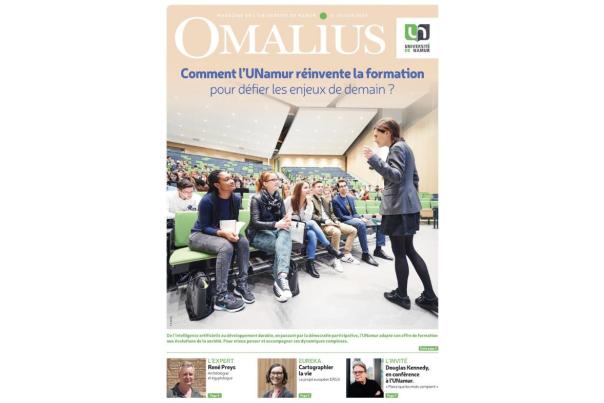

O. : As you visit our university to share your experience, what message would you like our students to take away?

D. K. : When you read a novel, you ask yourself questions. That's what I hope for my readers, whether they're academics or not: that they ultimately nourish themselves with my novels. I write about serious things, but I also write to keep the reader turning the pages. I'm an advocate of "popular" literature. And I'm committed to demystifying culture and literature. It's essential to create a new generation of readers. Reading is an escape. When a totalitarian regime is set up, writers are among the first people to be silenced. Why is this? Because words matter, and because most writers don't have a Manichean vision of the society in which they find themselves. The university has the same mission. That of opening others up to the world.

Interview by Anouk Delcourt (Point Virgule Bookseller) and Noëlle Joris