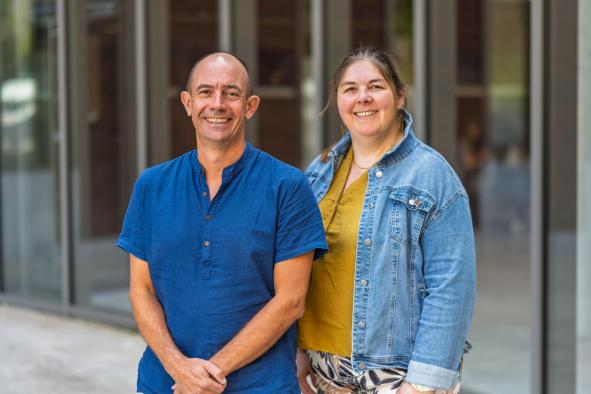

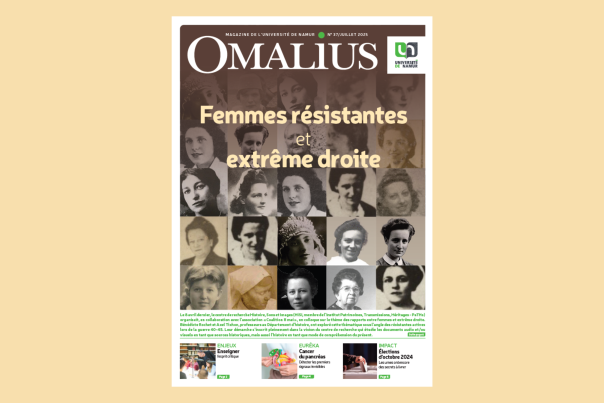

Resistance women have often been invisibilized, how do you explain this?

Bénédicte Rochet: First of all, there are factors specific to the history of Belgian resistance and politics. In the aftermath of the 2nd World War, the government had to deal with thousands of resistance fighters, some of whom were armed, while others were part of the Front de l'indépendance, a predominantly Communist network whose size raised fears of revolution in our country. Churchill and Roosevelt urged the Belgian government to take back the reins of power and maintain order, relying on official police forces and the Belgian army. In this context, the resistance was denigrated and, above all, disarmed.

From November 1944 onwards, resistance fighters demonstrated to gain recognition for their status. These demonstrations were to be swept under the carpet by the government and even the press. Even today, commemorations focus mainly on the army. And when we talk about the Resistance, we pay tribute to those who died during the war.

Many women, moreover, won't apply for status recognition because they don't identify with the military connotation associated with it at the time. What's more, since they often joined the resistance with the whole family unit, it was the father of the family who would submit the application for recognition. All this contributed to the invisibilization of resistance fighters.

A.T.: At the symposium, Ellen De Soete, founder of the Coalition 8 mai, gave a very moving testimony. She explained how her mother, an arrested and tortured resistance fighter, built her whole life on silence. Her ordeal was the consequence of the fact that others had spoken out. It was therefore essential for her to keep silent so as not to endanger her children. If they knew, they too might be tortured. It was only at the end of her life that she began to speak out. Ellen De Soete explained that, as children, their mother forbade them to go out or invite friends to the house. The scars caused by the war often went beyond the individuals themselves to have an impact on the whole family, including subsequent generations. It was this culture of silence that contributed to the invisibility of women resistance fighters.

B.R.: Starting in the 60s and 70s, there was a shift with gender studies. Studies would initially focus on women at work and women's rights, but not at all on their role in wartime contexts. It wasn't until the late 90s and early 2000s, therefore, that history turned its attention to women resistance fighters during the 40-45 war.