35 years between two accelerators - Serge Mathot's journey, or the art of welding history to physics

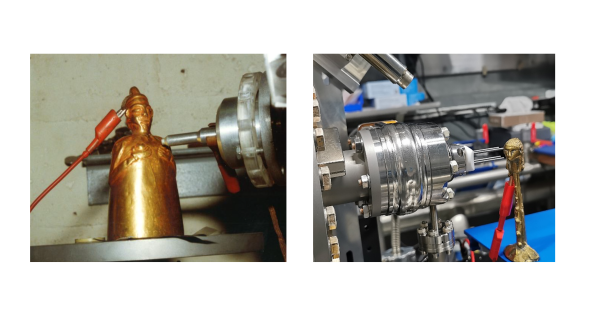

One foot in the past, the other in the future. From Etruscan granulation to PIXE analysis, Serge Mathot has built a unique career, between scientific heritage and particle accelerators. Portrait of a passionate alumnus at the crossroads of disciplines.