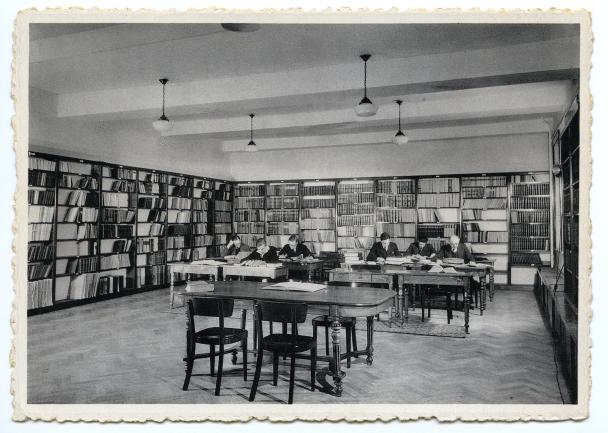

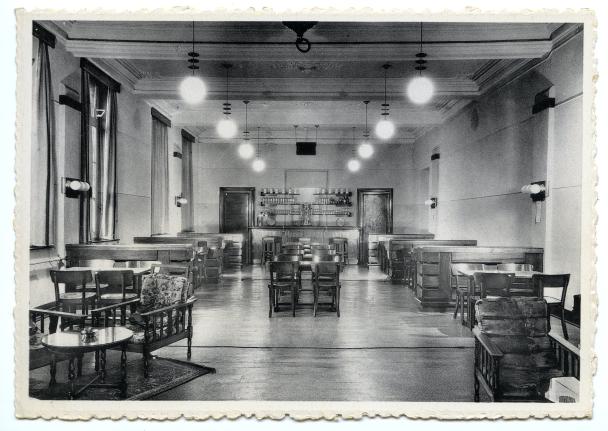

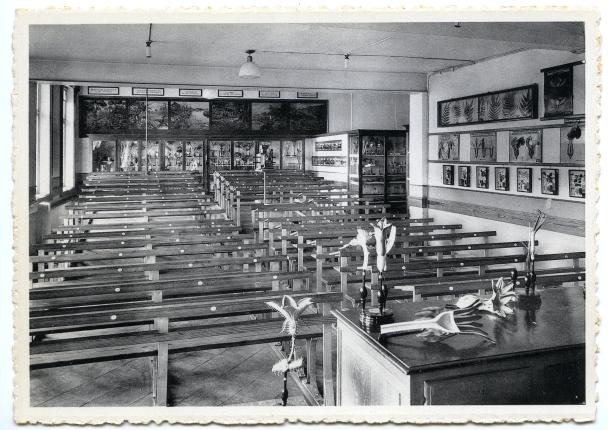

When UNamur told its story in postcards

The Moretus Plantin University Library (BUMP) at UNamur preserves a collection of several thousand postcards within its precious reserve. This remarkable collection offers an original insight into the daily life of the people of Namur in the 19th and 20th centuries. Some of these cards show the Faculties as they looked almost a century ago, and illustrate the teaching and research activities that were carried out there at the time.